Insights

Taking Action under Pressure

Ideas on how approaches from busines help tackle pressures in everyday life.

When Momentum Fades

Why energy and discipline are not the problem

January 2026

When momentum fades, people often assume the problem is energy or discipline. But these are usually symptoms, not causes. Momentum declines when something doesn’t make sense, stops paying off, or starts demanding more than expected.

Here are some common sources of lost momentum.

- Opinions: Negative or conflicting voices require effort to process and, at times, to stay engaged.

- Size and complexity: When something turns out to be bigger or harder than expected, pushing through demands more energy and focus than planned.

- Worries: A troublesome uncertainty or “what if” can drain energy and enthusiasm.

- Resources: Doubts about skills, time, or support consume energy to hedge, delay, or over-prepare.

- Invisible progress: Effort without visible payoff can make work feel endless and require increasing amounts of discipline to persevere.

- Changes: Shifting priorities or circumstances can change expectations, demanding discipline to adjust course.

Try this

Instead of pushing through when momentum fades, try diagnosing what’s actually happening. A few questions often surface the issue.

- If others’ voices are distracting you, it’s probably an opinions problem.

- If something feels bigger or harder than expected, you’re likely dealing with a size or complexity problem.

- If an uncertainty or “what if” keeps demanding your attention, it’s a worry problem.

- If you’re hesitating because you’re unsure you have what you need (time, skill, support), it’s a resources problem.

- If you’ve been working steadily but see no headway, it may be an invisible-progress problem.

- If the work feels less relevant or off track because things have shifted, you probably have a change problem.

Knowing that a loss of momentum isn’t about a broad trait like motivation or discipline makes it easier to address. It also helps you focus on the right problem so momentum can return.

Example

Momentum on creating a large backyard garden has stopped. After running through the questions, the issue is complexity: creating a garden that won’t get eaten by deer and can be watered reliably is far harder than expected. A smaller, deer-resistant, drought-resistant garden now makes more sense.

Note

There are many ways to address these problems. PMEZ offers one way through its guides.

Begin With the End in Mind

You can't finish what isn't defined

January 2026

When people decide to make something happen, bring an idea to life, or work toward an important goal they often jump straight to action. Meetings are set up, supplies are purchased, content is created.

But without a clear picture of the end result, effort can be wasted in the wrong places and resources spent on the wrong things. The line between making progress and being busy can blur.

That’s why defining done before taking action is so important.

Done is not a task list. It’s the concrete end result you’re trying to reach. It’s the finish line you’ll recognize when you cross it.

When done is clear:

- Decisions get easier, because you have something to aim for.

- Tradeoffs make more sense, because you know what matters to the outcome.

- Motivation lasts longer, because you’re working toward a real result.

Try this

Write one sentence that describes what done looks like for something important you are working toward.

Then check:

- Is it observable? (It’s a “something” and not an action or task.)

- Is it realistic? (It fits your time, energy, skills, and budget.)

- Does it have a clear finish line? (You can pinpoint when you’re complete.)

If you can answer yes to all three, you’re ready for serious action.

Example

The president of a local club wants to simplify coordinating volunteers for their five annual fundraisers. She defines done like this:

Done is when a volunteer page can be configured for different events that members use for sign-ups.

From PMEZ’s DONE approach

Why Decisions Feel Hard

When there is no ideal option

January 2026

Decisions become hard when no option can give you all you want. You want to volunteer, but you don’t want to give up your evenings. You want to move, but you don’t want to uproot your kids. You want a pet, but you don’t want to lose your freedom.

When this happens, a natural reaction is to list more pros and cons, do more research, or have more conversations. But that misses the real problem. The difficulty isn’t lack of facts. It’s a conflict between what matters to you.

Instead, focus on your drivers: the results you’re trying to protect, gain, avoid, or preserve. Spend your energy deciding which drivers must guide the decision, and which can only support.

Try this

-

- Write down a decision that’s hanging over you and list the options.

- For each option, ask: “If I choose this, what am I trying to protect, gain, avoid, or preserve?” Those answers are drivers.

- Pick the one or two drivers you would truly regret ignoring.

- Use those drivers to make the choice.

Example

-

- Decision: Should I take on a weekly volunteer role or not?

- Drivers: Protecting weeknights for family, supporting a cause I care about, staying connected with the community, learning new skills.

- Guiding drivers: Protecting my weeknights and supporting the cause.

- Choice: Don’t take the weekly role. Find another way to help.

Start with 'What'... not 'How'

Understand the challenge then pick the approach

December 2025

Advice often starts with how.

-

- How to prioritze your efforts.

- How to reach a goal.

- How to launch a business.

But when people face a challenge, how is often the wrong place to start. It assumes an approach without understanding what the problem is.

Sometimes the problem is pressure from everyday life. You have too many important decisions to make. Too many things to do at once. Too many opinions to reconcile.

Sometimes the problem is finishing something that matters. You have important ideas and goals, but you never quite finish them. You’re busy, but progress is uneven. You’re halfway done, but you run out of time, money, or interest.

And sometimes the problem is the sheer size of what must be done. The work involves many people, moving parts, resources and expectations. And it lasts for months and months.

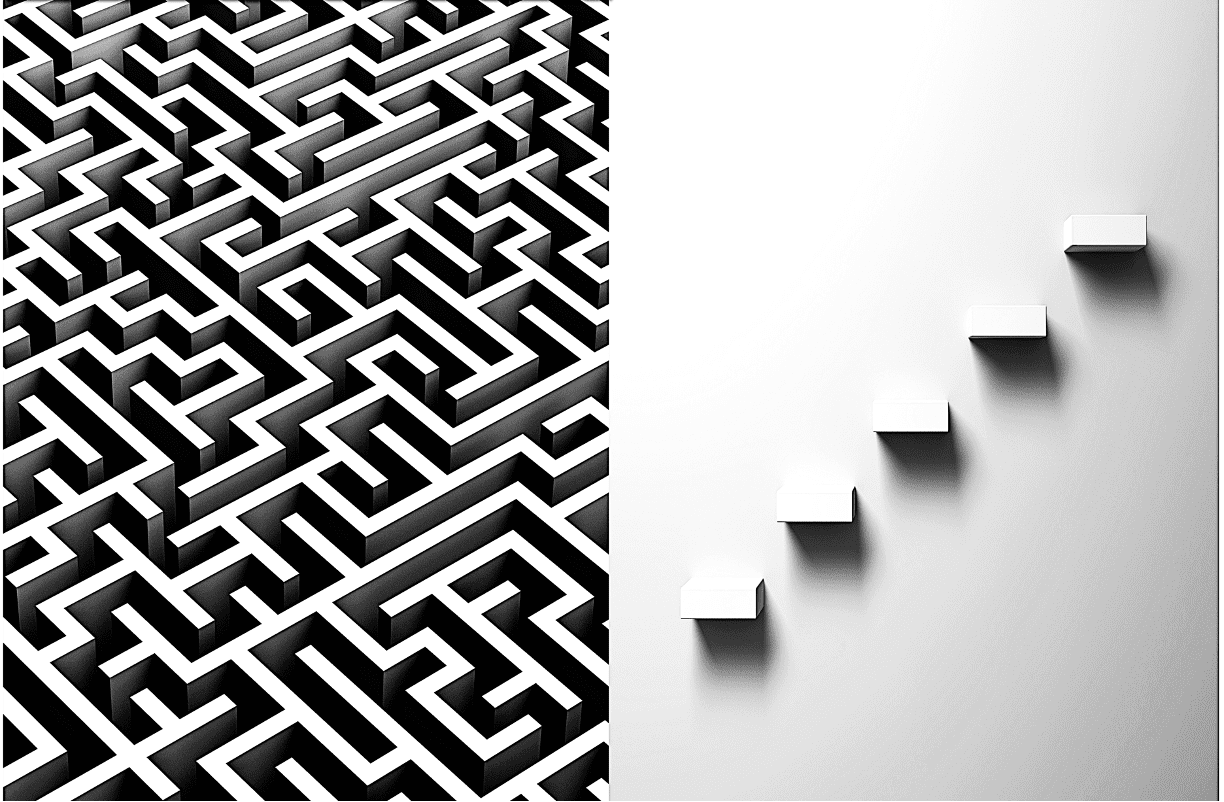

These are three different problems that need three different overall approaches:

-

- techniques to deal with everyday pressures.

- steps to achieve something important.

- structure to coordinate many people working on something big.

Start by understanding what the problem is. Then decide how to proceed using either a simple technique, coordinated steps or an integrated structure.

When Opinions Derail Progress

Handle opinions by role, not person.

December 2025

When you’re doing something that matters, people will have opinions. Some are useful. Many aren’t. If you treat all input as equal, you can get pulled off course, slow down, or end up optimizing for someone else’s preferences instead of your own.

A practical way to handle this is to decide who has a say based on their role in what you’re trying to achieve.

-

- Engage: directly affected or accountable for the outcome. They get a say.

- Target: helpers or experts. They get a say only in their lane.

- Sincerely acknowledge: everyone else. You listen, thank them, and move forward as you see fit.

This isn’t dismissive. It’s how you keep the right people involved, ensure quieter voices aren’t drowned out, and avoid spending energy on unnecessary justifications. It’s also how you prevent “whoever talks the most” from steering your efforts.

Try this

- Pick one goal you care about.

- List every person who has offered input, might offer input, or should have input but hasn’t weighed in.

- Then label each person as Engage, Target, or Sincerely acknowledge.

Example

Planning a wedding

- Engage: the couple and those paying

- Target: the friend doing flowers (flowers only), the musician (music only).

- Sincerely acknowledge: the cousin with strong opinions about “what weddings should be.”

From PMEZ’s DONE approach

Worries Feel Personal But Act Like Risks

Worry is uncertainty. Risk is uncertainty with a response.

November 2025

Worry shows up as a voice in your head, so it can feel personal. It’s thoughts of what could happen. What if it rains at the fair? What if the car breaks down again? What if I finish late?

When someone shares a worry, the response is often: “don’t stress,” or “it’ll be OK,” which means well, but avoids addressing the concern. Without a way to talk about uncertainty, worry stays personal and can grow.

But in engineering and project work, “it’ll be OK” is not an appropriate answer. If a builder is worried the beams are too weak for the skyscraper, nobody says, “try to relax.” The worry gets stated, assessed, and handled.

Worries and risks are both about uncertainty. The difference is what you do next. Risk is worry that’s been pulled out into the open and addressed with the right amount of action. Any uncertainty, at home, at work, at school, can stay as worry, or it can become a risk you can respond to.

Try this

- Write a vague worry as a specific risk

- Pick one small action that reduces the likelihood it occurs.

Example

- Vague worry: I might mess up the presentation

- Risk: I might run long or I might sound nervous

- Action: Rehearse out loud with a few friends and a timer.

Practical Project Management

Collaboration Can Matter More than Methodology.

October 2025

Many small organizations don’t have the time for project management. Their people are too busy for a new vocabulary, a stack of templates, or complicated tools.

But they still want their projects to move fast.

A lightweight project structure practical for smaller organizations can be defined. But structure alone doesn’t guarantee success.

In reality, projects succeed or fail based on collaboration skills. When those skills are strong, a lightweight approach works fine. But when they’re weak, a project can stall because the problem isn’t method. It’s how people are working together.

Three skills matter more than most teams think:

Communication that actually transfers information:

Not updates. Not long emails. Not meetings that end with “great discussion.” Real communication that pulls the right information out early, catches misunderstandings before they become rework, and explains decisions clearly enough so people can act.

Conditions that encourage contributions:

Teams in smaller organizations tend to be ad hoc and overloaded. Priorities shift. Dependencies multiply. Someone has to provide direction when things are confused, make it OK to surface issues, and care about morale.

Conflict handling before it turns into delay:

Most conflict isn’t a big blow-up. It’s side conversations, quiet resistance, and small disruptions. Skill at detecting disagreements and resolving them will keep people working effectively together.